Farming Shrimp, Harvesting Hunger: The Costs and Benefits of the Blue Revolution

Food First Backgrounder, Winter 2002, Vol. 8, No. 1

Not long ago, shrimp were considered a rare and expensive delicacy. Not anymore. Thanks to soaring demand from the US, Japan and Western Europe, shrimp are now raised on an industrial scale in tropical countries. Today shrimp rival tuna as the most popular seafood consumed in the US. The dramatic growth in the consumption of shrimp is due to its increasing affordability. The sharp decline in the price of shrimp over the last few decades has been driven by increased production, propelled by the lure of exporting shrimp to earn foreign exchange, and stiff competition among the producers along the tropical coasts of Asia, Latin America, and Africa. Industrial shrimp farming is quite distinct from the subsistence, traditional, or artisanal aquaculture that has been practiced for millennia by local people in Asia and elsewhere.

Industrial shrimp aquaculture is an integral part of the so-called Blue Revolution—the concerted effort to increase the industrially farmed production of a diverse array of aquatic species. Like the earlier Green Revolution, the Blue Revolution is frequently promoted as a way to help feed the world’s hungry by increasing the supply of affordable food. The results of the Blue Revolution have been exactly the opposite. As the earlier Green Revolution was necessary to establish the global corporate agro-food system, the Blue Revolution is an essential part of integrating aquatic species (including cultured shrimp) and coastal ecosystems into that same global food production system. Hundreds of national and multinational corporations, financially strapped national governments, and international development and donor agencies have promoted the expansion of industrial shrimp farms. They justify their efforts on the grounds that shrimp farming can contribute to the world’s food supply by compensating for the decline in capture fisheries, generate significant foreign exchange earnings for poor Third World nations, and enhance employment opportunities and incomes in poor coastal communities.

Recent industry projections estimate that farmed shrimp will account for more than 50 percent of total global production within the next five years.

The increasing popularity of industrially cultivating shrimp began in the early 1970s. Back then, total world production of shrimp, almost all from wild capture fisheries, was around 25,000 metric tons. Today total world production is close to 800,000 metric tons, about 30% from shrimp raised on farms in more than 50 countries. Recent industry projections estimate that farmed shrimp will account for more than 50% of total global production within the next five years. While approximate ly 99% of farmed shrimp are raised in developing countries, almost all of it is exported and consumed in rich, industrial countries—the US, Western Europe and Japan.

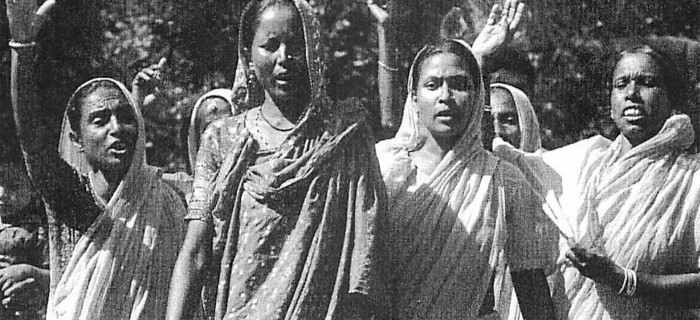

The explosive growth of the aquaculture industry has generated mounting criticism over its social, economic, and environmental consequences, and has provoked the establishment of hundreds of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) at the local, national, and international levels. Escalating conflicts between critics and supporters of industrial shrimp farming have transcended local and national arenas. In 1997 these conflicts catalyzed the formation of two major global alliances: The Industrial Shrimp Action Network (ISA Net) composed of environmental, peasant-based, and fisher-based NGOs opposed to unsustainable shrimp farming, and The Global Aquaculture Alliance (GAA) made up of industry groups created to counter the claims and campaigns of this activist ISA Network.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.