The Campesino a Campesino Movement: Farmer-led sustainable agriculture

By Eric Holt-Giménez, June 1996, Development Report No. 10

Introduction

“Farmers helping their brothers so that they can help themselves to find solutions and not be dependent on a technician or on the bank. That is Campesino a Campesino.”

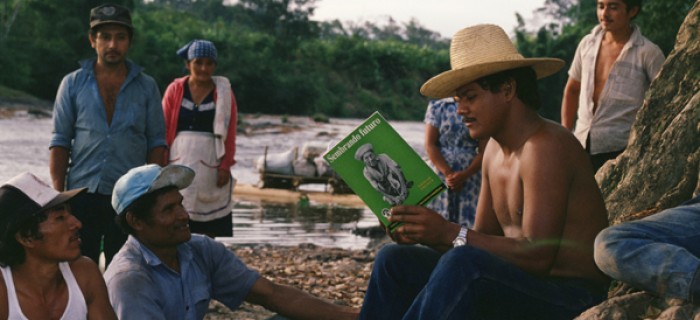

This is the simple definition provided by a farmer for the grassroots movement in sustainable agriculture that has swept across Mexico and Central America. El Movimiento Campesino a Campesino, or the Farmer to Farmer Movement, is one of the most extensive and successful efforts for sustainable agriculture to appear in Latin America in decades.

Led by campesino, the subsistence farmers of the ecologically fragile hillsides and forest perimeters of the Mesoamerican tropics, Campesino a Campesino (CAC) involves hundreds of volunteer and part-time campesino “promotores” with the support of dozens of technicians, professionals and local development organizations. Participants number in the incalculable thousands. Incalculable because in essence, Campesino a Campesino is an extensive, expanding and somewhat amorphous cultural process for agricultural transformation. Programmatically elusive and annoyingly asystematic, Campesino a Campesino has nonetheless succeeded in regenerating tens of thousands of hectares of exhausted soils in the tropics. Simultaneously, it has significantly raised and stabilized campesino agricultural production. opening the door to crop diversification, marketing. processing, commercialization and other alternatives.

How have campesinos helped each other develop sustainable agriculture? On the one hand, they have used relatively simple methods of small-scale experimentation, combined with horizontal (farmer to farmer) workshops in basic ecology, agronomy, soil and water conservation, soil building, seed selection, crop diversification, integrated pest management, and biological weed control. These approaches have provided campesinos with sufficient technical and ecological knowledge to reverse degenerative agroecological processes and overcome the basic limiting factors in farm production.

Campesino a Campesino has succeeded in regenerating tens of thousands of hectares of exhausted soils in the tropics and stabilized campesino agricultural production while opening the door to crop diversification, marketing, processing, commercialization and other alternatives.

Stay in the loop with Food First!

Get our independent analysis, research, and other publications you care about to your inbox for free!

Sign up today!On the other hand, campesino promotores, leading by example, have inspired their peers to innovate and try new alternatives. This inspiration has given them the conviction, enthusiasm and pride to teach others using hands-on learning methods, and to share with others through farmer to farmer cross-visits and conferences. By forging their own alternatives for agriculture, the promotores have gained a new-found belief in themselves and have formulated a fresh, campesino vision for the future of agriculture. Campesino a Campesino is not so much a program or a project looking for peasant “participation”; it is a cultural phenomenon, a broad-based movement with campesinos as the main actors. As protagonists, they are foremost and directly involved in all stages of generation and transfer of technologies for sustainable agriculture including adoption and adaptation of appropriate modern techniques as well as traditional practices.

This approach is fundamentally different from the conventional “generation and transfer” strategies for agricultural development applied by governments and research centers for nearly half a century in the developing world. Granted, the “old” conventional approach has evolved from the top-down extension of technological packages to “passive” farmers, to sophisticated “new” conventional approaches which use “participatory” techniques to elicit farmer involvement. What remains the same is the conventional chain of command and control over research & development, generation & transfer process: researchers and governments ultimately control the agenda and resources, whereas farmers “participate.”

While this approach was, by its own criteria, effective for the once-touted “Green Revolution,” it has fallen flat for sustainable agriculture. With a few exceptions, campesinos are simply not adopting techniques pushed by the international research centers and state extension progra1ns. In the face of the growing agroecological crisis sweeping Latin America, solving the “problem” of farmer participation has become a critical issue for both technicians and researchers.

The Campesino a Campesino movement does not presume to solve the problems of governments or research centers for them. It simply turns the fundamental question on its head. Rather than asking “how to get farmers to participate,” it poses the question: “How do those interested in the development of sustainable agriculture participate in farmer-led development?” A closer look at the movement may help to understand the question and formulate possible answers.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.